April 11, 2016

Disclaimer: SickNotWeak does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This content contains explicit and sensitive information that may not be suitable for all ages.

My undergraduate experience is bubble-wrapped; it fits me snug in all the right places, including extra time on assignments, notetaking, and exclusions from morning classes. I’ve really only heard of the harshness associated with the University of Toronto from a second-hand source. I was probably busy writing my exams with plushy headphones on, in a sound-proof room. One time, my professor even brought me a cookie because I was anxious. If I had a cookie for every anxiety attack I’ve had at U of T, I would probably outweigh our school mascot – a giant trash panda named Rex the Raccoon. I like to use the term “trash panda” to give Rex the exoticism he so rightly deserves.

I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder when I was seventeen, attempted suicide for the first time at eighteen, was seriously hospitalized for the second by the time I was twenty and had dropped out of school twice by twenty-one. I’ve been on so many medications that I’ve lost count; I’ve dropped weight and gained weight and fought it off just long enough to remember what it felt like to be one person instead of a spectrum, alternately smiling and waving and crying, depending on where the sunlight hit.

I don’t talk about it much. I also don’t talk in class much either, because my meds tend to give me “drunk mouth” in the mornings. My psychiatrist recently took me off Lamotrigine (it was turning me purple) and put me on Epival (so now I’m losing my hair), and when I later complained that my 10:30 am class attendance was suffering as a result, he beamed and said, “I’ve got something for that!” I’m now taking daily narcolepsy medication and questioning the entire psychiatric field.

It was one of the most glamourous days of the year in our ever-growing English department – the Humanities Conference. The conference is a celebration of all things liberal arts – narrative analysis, creative writing, overuse of the word “pedagogy”, and the slim chance of financial compensation for said academic pursuits. I participated last year – and that’s an action verb that isn’t always associated with my scholarly contributions. It’s amazing what free paninis can do for one’s intellectual drive.

The conference featured academic and creative presentations from U of T students, and a keynote speaker, whom I conveniently missed. The theme was “Crossing Borders,” and it felt suitable for the occasion. For me to even be here, voluntarily speaking in front of a crowd, was kind of a big deal. Because sadly, my disability accommodations do not include crowd control at school-wide events, and I was reading my story with no safety net.

I find academia intimidating for a number of reasons. People throw around big words that I’m afraid of, criticize people for having the wrong ideas – or worse, no ideas – and operate on a system of hierarchies that I don’t understand. I enjoy a lot of the reading I do for my still-in-progress English degree, but I never particularly identify with anyone from “the canon.” Mental illness has only recently been taken off the no-fly list of literature, and most of the autobiographical stories I see are told in retrospect, in a gentle (albeit patronizing) voice that assures you that you will get through this. As a result, I often don’t get through these books.

I arrived at the conference fashionably late, and slipped into the room between panels, shoving a few bottles of getaway juice into my purse. The only seats left were in the front row, a place I usually avoid like book-to-movie adaptations and flavoured Cheetos. The projector screen heralded the title “Mental Illness and the Dramatic Monologue,” which sounded like the name of a lecture that I skipped last term. My inner mental health advocate was extremely pleased to see some representation of mental health issues, but a bigger part of me hoped the talk wasn’t about bipolar. There’s something so alienating about understanding yourself one way, and seeing yourself presented in another. My health has been so fluid that I long for my identity to stay static, to ensure that one part of me is real.

The presenter was a graduate student with the kind of purple hair my mom forbade me from in Grade Ten. He addressed us confidently, drawing vague parallels between therapy and soliloquies and artistry as treatment, and I silently wondered if I should try yoga again, even though last time, I had walked out. The ambient sounds of the studio had overwhelmed me and infiltrated my lungs until I was certain that there was no room left to breathe. Somewhere in the differentiation between mental health and physical health, an idea emerged that we, the sick, could do more for ourselves – and for some reason, yoga seems to be the Nike swish of mindfulness.

The screen faded to black. The purple-haired presenter suddenly wheeled towards the back wall. I became aware of an immeasurable frequency in the air. Something different. Something sharp. His breath became ragged as he ran his hands over his knees in a jerky, repetitive motion, turning around to face us with hunched shoulders and blank eyes. He was transformed; his natural ease gone, replaced with something I couldn’t put my finger on. I felt it too, unfurling around my heart – not quite danger, but perhaps the sensation of being hunted.

I glanced around the room to see if anyone else had felt the change. Eyes were riveted on the purple-haired man, the listless veil of intellectualism swept aside for something more impassioned, more savage, more suited for primetime TV. From a worn-down office chair, he performed the one-sided conversation of a patient with his doctor, the occasional shudder escaping his body as he crammed jellybeans into his mouth by the fistful. The blue ones gave him nausea; the purple, nightmares. The yellow, I don’t remember what they did, but I knew I had tried them. My voice, emerging from his lips like a hackneyed puppet.

He stood up, fingers twitching and eyes wild, marching along the length of the front row, addressing each of us in turn.

“Do you feel sad?”

Fingers scraped against the plastic of my chair, teeth clenched.

“Do you feel guilty?

My breath was shards of glass in my throat.

“Do you feel worthless?”

He was standing in front of me now, dark eyes probing mine like scalpel on stone, waiting for the resounding “yes” that would confirm all of the medically supported reasons why I would never be safe here in this rigid room of academics. It didn’t matter what rainbow assortment of pills I took – I would never be enough on my own. My victories felt hollow, felt fixed, felt like something handed to me as a consolation prize for my sanity. I hadn’t told my professors yet, but I had just been awarded the top scholarship in my incoming Master’s class. I hadn’t told them because it was just another thing that I could give up on.

Vacant and graceless, I sat in the straight-backed chair and awaited my sentence.

“Are you afraid of the dark?”

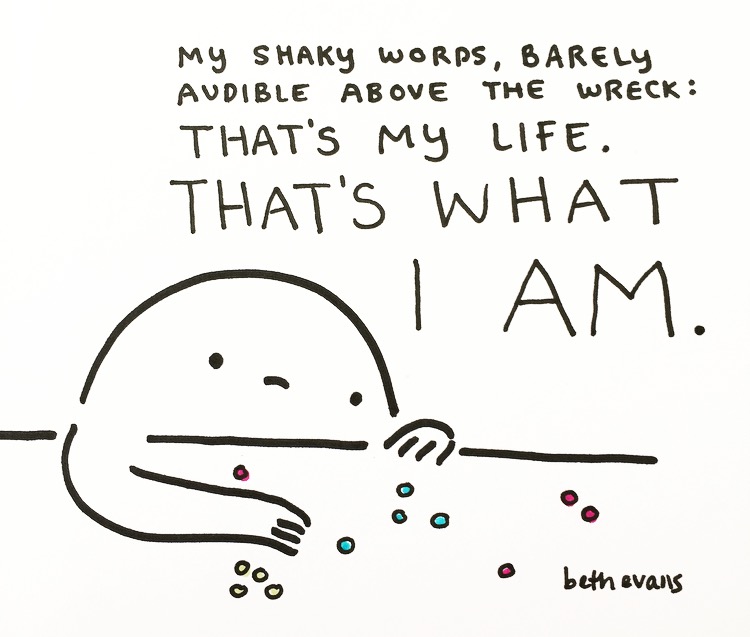

The first sob escaped my body like the soft hissing of a balloon, followed by another, a racking, guttural sound that shook my lungs. My professors hustled me out, away from the curious stares flung in my direction. My shaky words, barely audible above the wreck: That’s my life. That’s what I am.

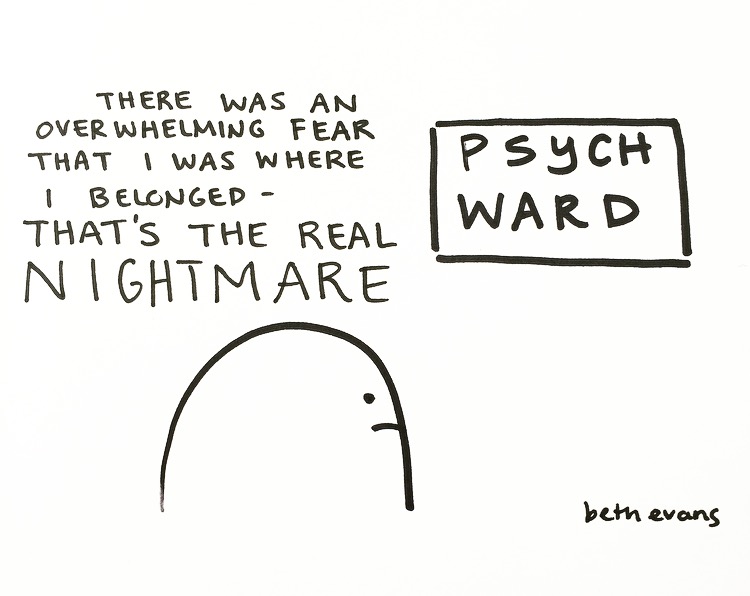

I spend my nights reliving the tenth floor of Rouge Valley Hospital, a place where I hovered somewhere in between sick and well – the patients thought I was a narc, and the nurses thought that I was faking. There’s no faking when there’s a cut in your wrist the length of a paperback novel. Sometimes stories do fit the mold. There’s a scene on the cutting room floor, shot the night before the conference. It was a scene where I crawled into my parents’ room at 1 am, sobbing hysterically over the small capsule I held in my hand – a flat, chalky, pill I had been staring at for hours but couldn’t take, a pill that looked like the sterile walls of the psych ward, the distorted faces seething against the glass of the emergency unit door, the overwhelming fear that I was exactly where I belonged. That’s the real nightmare.

He finished his presentation before coming to check on me, his face streaked with black paint.

“Are you okay?”

“Why is your face all black?” I asked, feeling numb.

He explained that it symbolized the scars that depression leaves on the mind and body, then asked for my email so we could talk about it more in-depth. I politely declined.

I learned later that he was an exchange student studying medicine who desperately wanted to dip his toe in the humanities pool before pursuing psychiatry at a post-doctoral level. And that’s the thing – most doctors I’ve had, were not treating me from a place of experience. It’s textbook authority on something that can’t always be learned. Mental illness is a sickness, but it can short-circuit the emotions, and people often get confused about the root. They make assumptions.

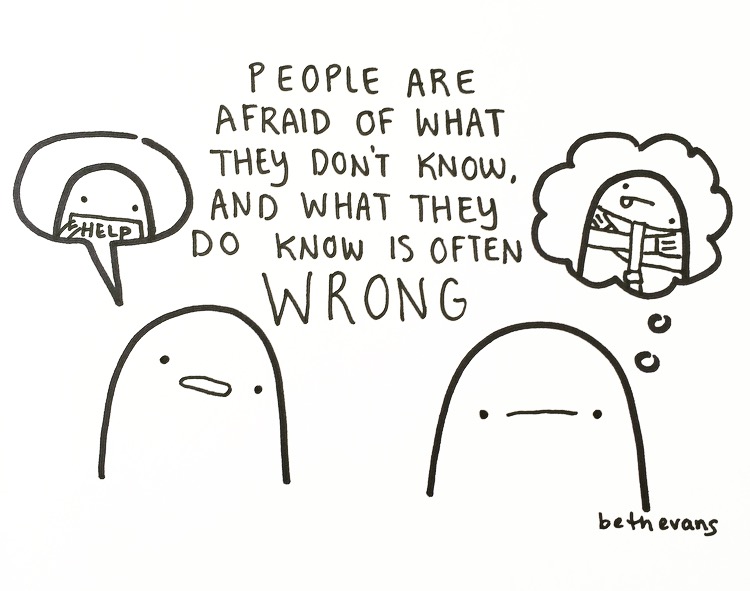

But I knew better than most how damaging these unfounded, negative representations of mental illness could be. I’ve seen it in the way a boy starts to look at me differently, halfway through our date. I’ve felt that imperceptible coldness that comes with asking for workplace accommodations. People are afraid of what they don’t know, and what they do know is often wrong. Anxious people don’t need jellybeans and doctor’s office props to demonstrate who they are. They just need a chance to speak for themselves.

I returned to the conference room mostly because my juice stash was there. I walked in with my head down, back tight, tears closing off my face like caution tape. I stepped carefully around my original chair and settled in another for the question period.

“Did you ever consider the ethical considerations of this project?”

It was an old classmate, shooting daggers at the purple-haired presenter.

“What do you mean by ethical considerations?” he answered, blinking.

After an earthquake, there are always stories of survival – people crawling out from the smallest cracks in the soil to live again, to tell their stories and grow stronger for the next time the ground is snatched from beneath their feet. My moods aren’t something I can predict (let alone control), but what I can do is plant as many roots as I can, so I can always find a way back to myself.

After having a massive anxiety attack in a public place for very obvious personal reasons, I can honestly tell you that I was not the one who was embarrassed. One by one, my classmates crawled out of the darkest parts of themselves, cheeks blackened but taut, to fire off questions about the appropriation of mental illness and the importance of trigger warnings. I could not speak, not until the purple-haired man had retreated to his corner, but when I did, the only words I needed were thank you.